Modelling Spatial Patterns of School Choice

A couple of weeks ago I visited King's Department of Education to give a seminar I entitled Agent-based simulation for distance-based school allocation policy analysis. The aim was to introduce agent-based modelling to those unaware and hopefully open a debate on how it might be used in future education research. This all came about as I've been working on modelling the drivers and consequences of school choice with Profs Chris Hamnett and Tim Butler here in King's Geography Department.

In their recent research, Chris and Tim looked at the role geography plays in educational inequalities in East London. Many UK local education authorities (LEAs) use spatial distance as a key criterion in their policy for allocating school places: people that live closer to a school rank get allocated to it before those that live farther away. This is necessary because it's often the case that more people want to send their children to a school than there are places available at it. For example, you can read about the criteria the Hackney LEA uses in their brochure for 2012.

Using data from several LEAs, Chris and Tim showed empirically how this distance criterion is related to school popularity. School popularity is indicated for example by the ratio of school applicants to the number of places available at the school (A:P) - some schools have very high ratios (e.g. up to 8 applications per place) and others very low (e.g. down to around one application per place). Furthermore, this spatial allocation criterion is an important influence on parents’ strategies for school applications, dependent on the location of their home relative to schools and their ability to move home.

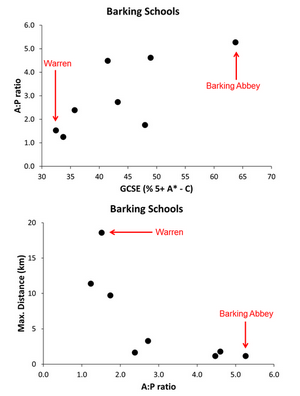

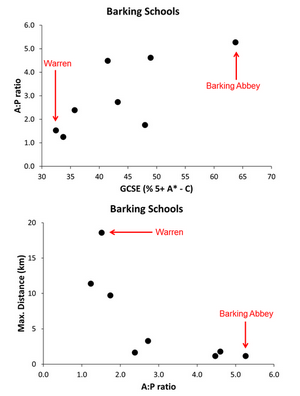

These allocation rules, combined with parent's strategies, produce patterns and relationships between schools' GCSE achievement levels, A:P ratio and the maximum distance that allocated pupils live from the school. In Barking, for example, we see in the figure below that more popular schools have higher percentages of pupils achieving five GCSE's with grades A* - C, and that these same popular schools also have the smallest maximum distances (i.e. pupils generally live very close to the school).

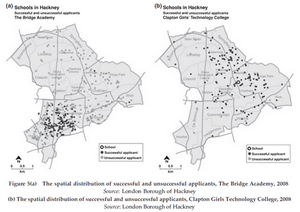

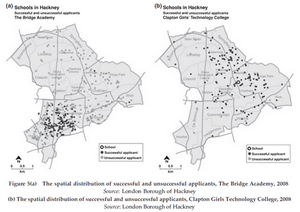

This spatial pattern can also seen when we look at maps of the locations of successful and unsuccessful applicants to popular and less popular schools in Hackney. For example, looking at the figure below (found in Hamnett and Butler 2011) we can see how successful applicants to The Bridge Academy (a popular school) are more tightly clustered around the it than those for Clapton Girls' Technology College (not such a popular school).

The geography of this school allocation policy, combined with differences in parents’ circumstances, suggests this issue is a prime candidate for study using agent-based modelling. Agent-based simulation modelling might be useful here because it provides a means to represent interactions between individual actors with different attributes (in this case schools and parents) across space and time. Once the simulation model structure (e.g. rules of interactions between agents) has been established, it can then be used to examine the potential effects of things like opening or closing schools (i.e. changes in external conditions) or changes in school allocation policy rules or parents’ application strategies (i.e. internal model relationships and rules).

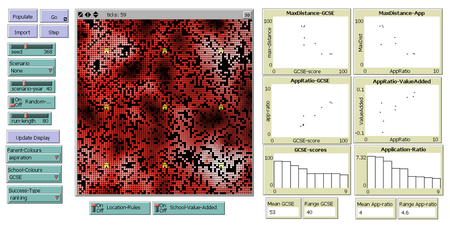

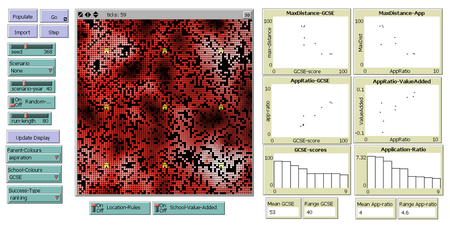

I developed an initial 'model' as a proof of concept and which you can try out yourself. Things have progressed from that proof of concept model, and the model now represents changes in cohorts of school applicants and pupils through time, including the potential for parents to move house to be more likely to get their child into a desired school.

In the seminar with the Department of Education guys I presented some ouput from the recent modelling. I showed how the abstract model with relatively few and simple assumptions can start from random conditions to reproduce empirical spatial patterns in school applications and attainment outcomes like those described above (see the figure below)

I also presented early results from using the simulation model to explore implications of potential policy alternatives (such as closing failing schools). These ideas were generally welcomed in the seminar but there were some interesting questions about the what the model assumptions might entail for maintaining existing policy assumptions and intentions (what we might term the rhetoric of modelling).

I'm exploring some of these questions now, including for example issues of how we define a 'good' school and how parents' school application strategies might change as allocation rules change. These will feed into a research manuscript that I'll continue to work on with Chris and Tim.

In their recent research, Chris and Tim looked at the role geography plays in educational inequalities in East London. Many UK local education authorities (LEAs) use spatial distance as a key criterion in their policy for allocating school places: people that live closer to a school rank get allocated to it before those that live farther away. This is necessary because it's often the case that more people want to send their children to a school than there are places available at it. For example, you can read about the criteria the Hackney LEA uses in their brochure for 2012.

Using data from several LEAs, Chris and Tim showed empirically how this distance criterion is related to school popularity. School popularity is indicated for example by the ratio of school applicants to the number of places available at the school (A:P) - some schools have very high ratios (e.g. up to 8 applications per place) and others very low (e.g. down to around one application per place). Furthermore, this spatial allocation criterion is an important influence on parents’ strategies for school applications, dependent on the location of their home relative to schools and their ability to move home.

These allocation rules, combined with parent's strategies, produce patterns and relationships between schools' GCSE achievement levels, A:P ratio and the maximum distance that allocated pupils live from the school. In Barking, for example, we see in the figure below that more popular schools have higher percentages of pupils achieving five GCSE's with grades A* - C, and that these same popular schools also have the smallest maximum distances (i.e. pupils generally live very close to the school).

This spatial pattern can also seen when we look at maps of the locations of successful and unsuccessful applicants to popular and less popular schools in Hackney. For example, looking at the figure below (found in Hamnett and Butler 2011) we can see how successful applicants to The Bridge Academy (a popular school) are more tightly clustered around the it than those for Clapton Girls' Technology College (not such a popular school).

The geography of this school allocation policy, combined with differences in parents’ circumstances, suggests this issue is a prime candidate for study using agent-based modelling. Agent-based simulation modelling might be useful here because it provides a means to represent interactions between individual actors with different attributes (in this case schools and parents) across space and time. Once the simulation model structure (e.g. rules of interactions between agents) has been established, it can then be used to examine the potential effects of things like opening or closing schools (i.e. changes in external conditions) or changes in school allocation policy rules or parents’ application strategies (i.e. internal model relationships and rules).

I developed an initial 'model' as a proof of concept and which you can try out yourself. Things have progressed from that proof of concept model, and the model now represents changes in cohorts of school applicants and pupils through time, including the potential for parents to move house to be more likely to get their child into a desired school.

In the seminar with the Department of Education guys I presented some ouput from the recent modelling. I showed how the abstract model with relatively few and simple assumptions can start from random conditions to reproduce empirical spatial patterns in school applications and attainment outcomes like those described above (see the figure below)

I also presented early results from using the simulation model to explore implications of potential policy alternatives (such as closing failing schools). These ideas were generally welcomed in the seminar but there were some interesting questions about the what the model assumptions might entail for maintaining existing policy assumptions and intentions (what we might term the rhetoric of modelling).

I'm exploring some of these questions now, including for example issues of how we define a 'good' school and how parents' school application strategies might change as allocation rules change. These will feed into a research manuscript that I'll continue to work on with Chris and Tim.

This work by James D.A. Millington is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home